Post from the The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America forum

DriftScribe started reading...

The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America

Naomi Murakawa

DriftScribe wrote a review...

A quick nonfiction read that mixes art criticism with a kind of wandering through the city. Each chapter moves through the work and lives of different artists, using them as a way to think about loneliness. Through them, the author also finds her way around New York and places the subject within an urban setting. It’s great to know that travel essays haven’t died out from nonfiction writing.

What made me a little uneasy is that the book frames loneliness as something deeply personal, yet then goes on to probe the lives of these artists to trace it there. Reading it with that idea in mind sometimes felt like peering into their private wounds, almost as if I was intruding on something that wasn’t really meant to be looked at so closely. At times it even felt a bit invasive, as if loneliness was being uncovered in places where it might not have wanted to be named.

Also, being alone doesn’t necessarily mean being lonely, and loneliness itself isn’t always something negative. But throughout the book it’s mostly treated as something heavy and inescapable, almost like a condition people are stuck with.

DriftScribe finished a book

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

Olivia Laing

DriftScribe is interested in reading...

Nobody's Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice

Virginia Roberts Giuffre

DriftScribe TBR'd a book

Greater than the Sum of Our Parts: Feminism, Inter/Nationalism, and Palestine

Nada Elia

DriftScribe made progress on...

DriftScribe is interested in reading...

We Are Each Other's Liberation: Black and Asian Feminist Solidarities

Rachel Kuo

DriftScribe commented on a post from the Pagebound Club forum

i love that independent publishing houses invest in niche genres, authors of underrepresented demographics, and unconventional narratives. often they also offer authors better support and control over their work.

i’ve noticed a resurgence here in the UK since the pandemic slump, and have been trying to support them & advocate them as best i can!

some faves:

- Tilted Axis Press (mainly contemporary lit in translation from Asian authors)

- Fitzcarraldo Editions (ambitious, acclaimed, sometimes unconventional)

- Dead Ink (bold, experimental, often debuts)

- And Other Stories (diverse authors, boundary-pushing narratives)

it helps that all their editions are stunning!!

please do share any recs :)

DriftScribe started reading...

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

Olivia Laing

DriftScribe is interested in reading...

This is Going to Hurt: Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor

Adam Kay

DriftScribe wrote a review...

Very Remarkable analysis of how witch-hunting served as an exploitative tool in the primitive accumulation of capitalism. I'd argue that the definition of social reproduction in the book isn't clear enough and might miss some points because it focused too much on procreation. Still, the whole argumentation process is fascinating.

DriftScribe paused reading...

Actual Air

David Berman

DriftScribe commented on a post

“… there’s a thick thread of narrative by well-meaning white Westerners that exalts the native populations in so many parts of the world for standing up to the occupiers, makes of their narrative a neat reflexive arc in which it was always understood, by the colonized and (this part implied) the descendants of the colonizer, that what happened was wrong.”

It’s a very insightful critique. Those beautiful anti-colonial stories (often goes like: ppl were oppressed → they bravely stood up → everyone eventually agreed it was wrong ) are so neat and morally wrapped-up that let the colonized be heroic in a very clean, noble way, and it lets the descendants of colonizers picture themselves as having long understood the moral lesson. It’s a story that lets Western audiences feel reflective without ever feeling implicated, while the anti-colonial resistance in real history involved fear, violence, disagreement, and desperation.

So these polished stories, even when they’re meant to honor the oppressed, always end up rewriting the past in a way that makes it easier for Western readers to digest and absorb. And the power to frame the story still sits with the West.

DriftScribe commented on a post

“Real justice would look to restore people and communities, to rebuild trust and social cohesion, to offer people a way forward, to reduce the social forces that drive crime, and to treat both victims and perpetrators as full human beings. Our police and larger criminal justice system not only fail at this but rarely see it as even related to their mission.”

DriftScribe is interested in reading...

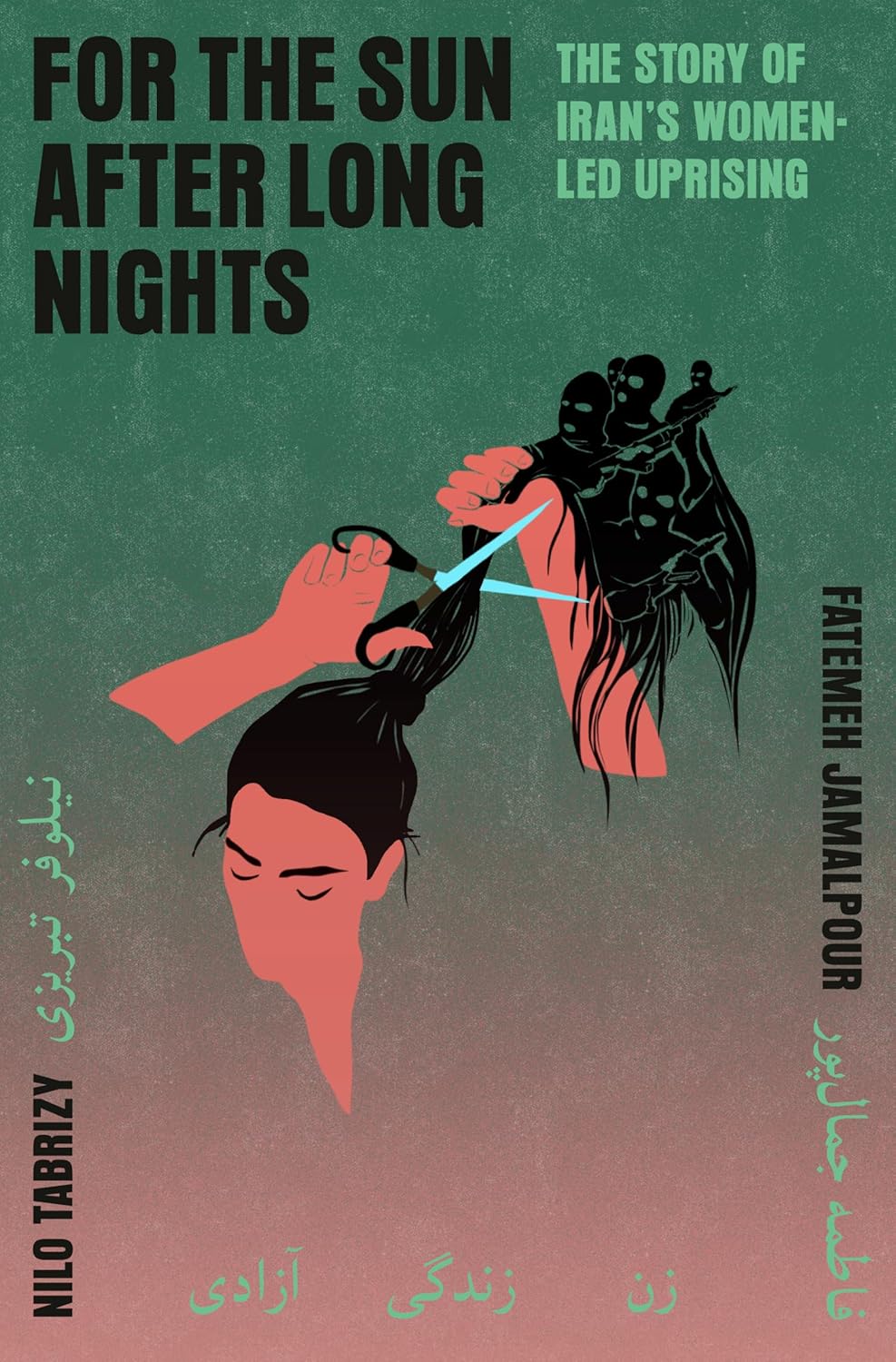

For the Sun After Long Nights: The Story of Iran's Women-Led Uprising

Nilo Tabrizy

DriftScribe commented on DriftScribe's update

DriftScribe started reading...

Actual Air

David Berman

DriftScribe started reading...

Actual Air

David Berman

DriftScribe is interested in reading...

The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States

Walter Johnson