stevehughwestenra started reading...

A Colder Home

Jillian Maria

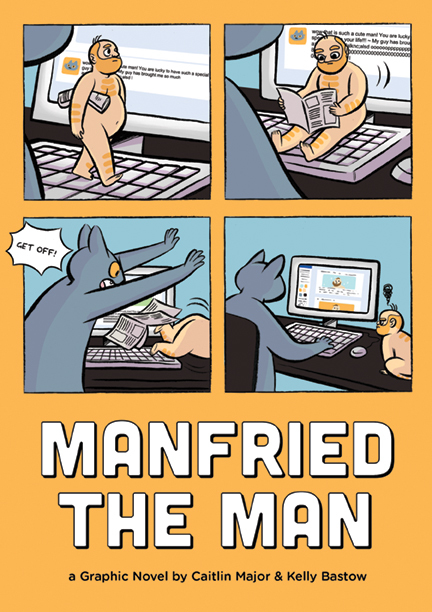

stevehughwestenra started reading...

Manfried the Man

Caitlin Major

stevehughwestenra finished a book

Ghost World

Daniel Clowes

stevehughwestenra commented on a post from the Pagebound Club forum

Hey y'all 👋🏻

It’s time for Who’s Who Wednesday where every Wednesday we introduce ourselves and make new friends. This is possibly part 15.

Jadelovesbooks originally started this. These were some of my favorite posts to read through so I'd like to bring it back if that's cool (or if these were ended on purpose, let me know and I'll remove this).

If you participated in any of the times before, you don’t have to introduce yourself again but you can share some different facts about you, an opinion you have, or how your week is going.

If you’re new, introduce yourself!

I’ll go first.

My name is Wibbily. When I listen to Good Luck Babe by Chappell Roan, I only hear 🎶"When you wake up next to ham in the middle of the night."🎶 I can't unhear it and now I kinda prefer it 🐷

stevehughwestenra created a list

Indie Ink Award Finalists - 2026

A list of all Indie Ink Award Finalists from 2026 that I could find on here (I'll add more as they're added to Pagebound--just let me know), minus any I'm aware used AI in any capacity (cover, etc)

0

stevehughwestenra created a list

SPFBO XI - Before We Go Blog

All the SPFBO XI books assigned to Before We Go Blog that I could find on Pagebound and that, to my knowledge, don't have AI covers or content.

0

stevehughwestenra started reading...

In Ice We Steel

Ayleen K. Kyrstin

stevehughwestenra wrote a review...

Read for SPFBO! Review to come!

stevehughwestenra finished a book

Knee-Deep in Cinders

Ashley Capes

stevehughwestenra wrote a review...

Originally posted on Before We Go Blog!: https://beforewegoblog.com/review-savage-daughters-of-the-secret-isle-j-patricia-anderson/

J. Patricia Anderson’s Daughters of Tith and Your Blood and Bones both impressed me with their smart worldbuilding, enchanting prose, and philosophical underpinnings, so Anderson’s third venture, Savage Daughters of the Secret Isle had a lot to live up to. Like Anderson’s horror-tinged, folktale-informed Your Blood and Bones, SDotSI is a novella, though for readers nervous about anything horror-related, I can reassure that in tone and subject matter, it has much more in common with Anderson’s epic fantasy work. Combining a LeGuinian use of the speculative to explore feminist philosophical themes with N. K. Jemisin’s incisive and clever worldbuilding, Savage Daughters of the Secret Isle blends the best of Anderson’s previous work while creating something startlingly new.

Savage Daughters of the Secret Isle is set in a secondary world in which magical ability has historically marked women as suspect and dangerous, and which has oppressed them violently over hundreds of years. While men with an affinity for magic have occasionally also been the subject of restriction (forbidden to marry or sire children, lest they pass on their talents, for example), they frequently retain a degree of power and respect that women do not, including access to higher learning and knowledge of more powerful magics. Witches—in contrast to wizards—have been burned, slaughtered, and exiled. Indeed, the dichotomy here mirrors to some degree real-world historical contrasts between licit and illicit forms of magic that were believed in during Europe and America’s Early Modern period, as well as how political power has historically been divided along gendered lines. SDotSI‘s story takes place not within the highly misogynistic society of the wider world, however, but outside it. On the shores of the titular Secret Isle, a community of magically-gifted women practices their arts in secret, living free lives with an emphasis on mutual respect, mutual support, and personal freedom. In many ways, SDotSI‘s worldbuilding literalizes folklorist Margaret Murray’s erroneous identification of a widespread historical witch cult in Europe, imagining a utopian, feminist version of the same. Denizens of the Secret Isle have found her shores in a variety of ways over many years, but the community remains small enough that there are concerns about its longevity. Protected by a sea monster that is controlled by one of the witches, many of the island’s inhabitants, including protagonist Rowan, were shipwrecked on the island’s shores. These wrecks have helped the island to remain hidden, with men typically left to drown. Rowan’s own magical affinity is for the ocean, and it is thanks in part to her talents that the community is able to sink ships. When a ship wrecks against the shores of the Secret Isle, but its magically-empowered wizard protects it, however, the community of women is forced to question the ethics of killing the survivors. Matters are complicated further when the ship turns out to be transporting a young woman with abilities similar to Rowan’s own. In the wake of the wizard’s survival, Rowan becomes increasingly tormented by the pressure to kill him, plagued by nightmares of her own drowned father and the mother and sister left behind.

Although I enjoyed Rowan as a character, SDotSI is very much a work focused on ideas, and it is for this reason that I would highly recommend it to fans of LeGuin, and particularly the LeGuin of The Dispossessed. Following the initial shipwreck, around the first half of the novella deals with the witches’ debates over how to deal with the unexpected survivors, as well as the overarching question of whether it is ever possible to truly retreat from the world (and whether one has an ethical responsibility not to). Since the witches themselves have come to the island at different points in time, they each come with their own experiences and baggage. While older members of the community, for instance, may have experienced gender-based violence at its most brutal, those like Rowan who are younger and grew up in a less violent world—or another girl named Parmenti, who was born on the island—may have limited memories or knowledge of oppression. Rowan and those like her therefore tend to express greater mercy than older community members, and she and Parmenti are considered “soft” by many of the other women. Without spoiling the details, at its most effective, SDotSI asks us to consider what different forms of activism can look like, when different approaches are needed, and what members of marginalized and oppressed groups who may have escaped oppression owe to those left behind.

One of the subjects Anderson tackles best is the question of isolationism. While hiding the island has been necessary in order for the women to survive and thrive, cutting themselves off from the rest of the world has repercussions both at a societal and personal level. More powerful magics that the older witches know to exist are inaccessible to them, while on a more intimate note, Rowan laments the loss of her extended family and feels guilty for the challenging lives she suspects her widowed mother and orphaned sister must have experienced. For all that Savage Daughters is a fantasy, it’s wrestling with questions and ideas that feel immediate and real. Though magic may not exist in our world as it does in SDotSI’s, misogyny certainly does, and Anderson tackles many real-world feminist issues alongside the speculative ones. The choices Anderson’s characters make are very narratively and personally satisfying, and though I won’t spoil them here, they do a great job asserting a clear position without coming off in any way as preachy or simplistic.

At the line level, Anderson’s prose ranges from the lush and poetic (Your Blood and Bones), to the restrained yet resonant (Daughters of Tith). Savage Daughters most resembles Daughters of Tith stylistically, privileging readability while reserving more evocative language for particularly momentous events and emotional moments. The writing here is clear and flows well, allowing the themes and subject matter of the novella to take centre stage. Nonetheless, Anderson always writes natural landscapes beautifully, and that remains true in Savage Daughters. Lyricism emerges at critical moments, but also lends the Secret Isle itself a grace that paints a vivid picture.

My own personal favourite moments in the novella arrive in its second half, when Rowan and her community come in closer contact with the ship and its occupants. The urgency introduced by the initial shipwreck returns here with a vengeance, as the planning and fretting of the witches rubs up against forces and people they can’t control. This development is mirrored in Rowan herself, who, the more she agonizes over the ship, begins to remember increasingly uncomfortable details about her own traumatic shipwreck, and to wrestle with issues of survivor’s guilt. Despite that Rowan is happy on the island, she nonetheless yearns for something beyond its shores, and separate from the protection of her found family. Her reminiscences here were especially moving, and Anderson’s use of Rowan’s story to underscore the themes she’s built up over the course of the book is highly effective. I will say that, while I didn’t dislike any of the characters, there were a fair number of supporting cast members, and in a short work, there wasn’t time to fully explore most of them. While the large cast felt realistic, naming a few fewer of the witches and emphasizing the personalities and backstories of the most significant might have been more effective given the short page count. Standouts from the supporting cast included Mal, Rowan’s much tougher close friend and somewhat of a surrogate sister and mother, and the witch on the shipwrecked vessel.

With Anderson’s beautiful writing and her considered approach to themes that feel especially relevant today, Savage Daughters is a fine addition to the subgenre of the critical feminist utopia. It manages to address key themes to do with gender and oppression without falling into the trap of essentializing gender, yet is also able to comment on more broadly applicable issues related to activism, safety, and community. I’ve recommended it to fans of LeGuin and Jemisin, as I’ve done with Anderson’s other work, but I’d further add that anyone who loves Jo Walton’s writing—especially her Thessaly trilogy—would do well to pick up Savage Daughters.

stevehughwestenra finished a book

Savage Daughters of the Secret Isle

J. Patricia Anderson

stevehughwestenra TBR'd a book

The Chamos Project

Alexis Ames

stevehughwestenra finished a book

Selkie Moon

Kelly Jarvis

stevehughwestenra finished a book

A Second Life Worth Living

Karen H. Lucia

stevehughwestenra left a rating...

stevehughwestenra finished a book

The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions

Larry Mitchell

stevehughwestenra started reading...

The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions

Larry Mitchell

stevehughwestenra is interested in reading...

Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993

Sarah Schulman

stevehughwestenra commented on a post

Jamie Bauer transitioned decades after their work in ACT UP, and now is nonbinary, but they came from the women’s peace movement and the lesbian activist community and functioned in ACT UP as an emissary of those legacies. Here I found that Nan Alamilla Boyd’s pioneering 1999 article “Looking for Lesbian Bodies in Transgender History” is very helpful to those of us telling lesbian and transgender histories through the same individuals. Jamie had particular experience in the Women’s Pentagon Action, in 1979, had great knowledge and commitment to nonviolence, and was learned and skilled in civil disobedience training from a feminist perspective. In fact, in our pretransition interview for the Oral History Project, Jamie details how they and others like John Kelley, BC Craig, Robert Vázquez-Pacheco, and Alexis Danzig (straight, bi, future trans, queer, gay, lesbian, white, Black, Brown, female, and male) educated ACT UP about nonviolent civil disobedience; organized and ran trainings for protesters, marshals, and legal observers; and basically supervised and organized ACT UP’s unwavering use of nonviolent civil disobedience.

I find Schulman’s language here TERF-y at worst and belabored at best. I don’t like the name of the article cited in the context of the TERF hysteria around “they’re trans-ing all the butches!” but, as far as I can tell, Boyd isn’t a TERF, just maybe playing on that language in the title of a trans-inclusionary theory/history. (I don’t have the institutional access I’d need to read these scholarly articles for myself.)

But in any case, I find it strange that Schulman felt the need to suddenly cite an article here. Her language throughout isn’t scholarly. I don’t recall her citing any other academic texts.

And the result of this suddenly “scholarly” use of language is strange. If Schulman’s language reflects Jamie Bauer’s, then that’s completely valid, of course! I’ve just never personally heard a non-binary person describe their journey with gender like this. It’s sometimes akin to “coming out”, as in, “I’m now sharing my real name/pronouns with you” or sometimes it’s more like “I’ve explored different gender expressions, and here’s where I feel comfortable (for now).” But I’ve never heard “I’ve been a Woman, but now I’m going to Transition and become a Non-binary.”

In any case, I just don’t think this whole discussion is warranted. It’s simply not confusing (or even surprising) that a non-binary person was involved in feminist & lesbian organizing. I’m reminded of Miss Major talking about being radicalized in a men’s prison or her son calling her “Daddy”. I don’t think anyone genuinely reacts to that with “But how, when you are a Woman???”

Super long post to call something belabored, hahah. This has been bothering me!